Utility room shelves complete.

Utility room shelves complete.

This one is odd, but it serves a purpose. We have an elderly cat who has bad joints so has trouble eating. I set out to create an adjustable tray so he didn’t have to bend down to eat. Here’s what I came up with. I made it tall enough to plan for the future (in case we end up getting a really large cat or a small dog someday in the future). Our cat can now comfortably eat while seated. The trays easily move up or down depending on the size of the bowl.

The inspiration for this: I had two Harbor Freight bar clamps in my shop, shown below, which I never use because I don’t like to use them for work holding. But the one thing I like about these is that the bottom clamp ratchet is very easy to move up and down. So I thought, what if I cut these clamps up and used the parts to make a cat feeder that could be adjusted?

This is the end result, with a touch of decorative cord wrapping. This was all made with wood scraps and it’s mostly poplar. I’m happy with how it came out and I believe it a one-of-kind design. I mean, really who is going to make something this weird?

Each tray is attached with four screws (and glued) to the aluminum clamp ratchets. I framed the trays so each has a lip so the cat can’t push the bowl off the edge.

I added bumper feet on the bottom of the stand to keep it off the ground a bit in case a water bowl is tipped. I made the top removable so each tray can be removed and cleaned. The tops are capped with scrap leather just to ensure we don’t cut ourselves on the cut aluminum edges. Each bar is set in the poplar base with deep mortises, glued, and screwed in. Also, I added wood inserts to the inner part of the bars for more sturdiness.

The top is shaped so it’s easy to lift off. I cut tiny mortises to fit these bits from the bar clamps and they just rest on top of the aluminum arms. I glued them in.

And here is the final. The apparatus is sized to fit nicely on a standard cat mat. I finished all the wood parts with three coats of Osmo TopOil High Solid.

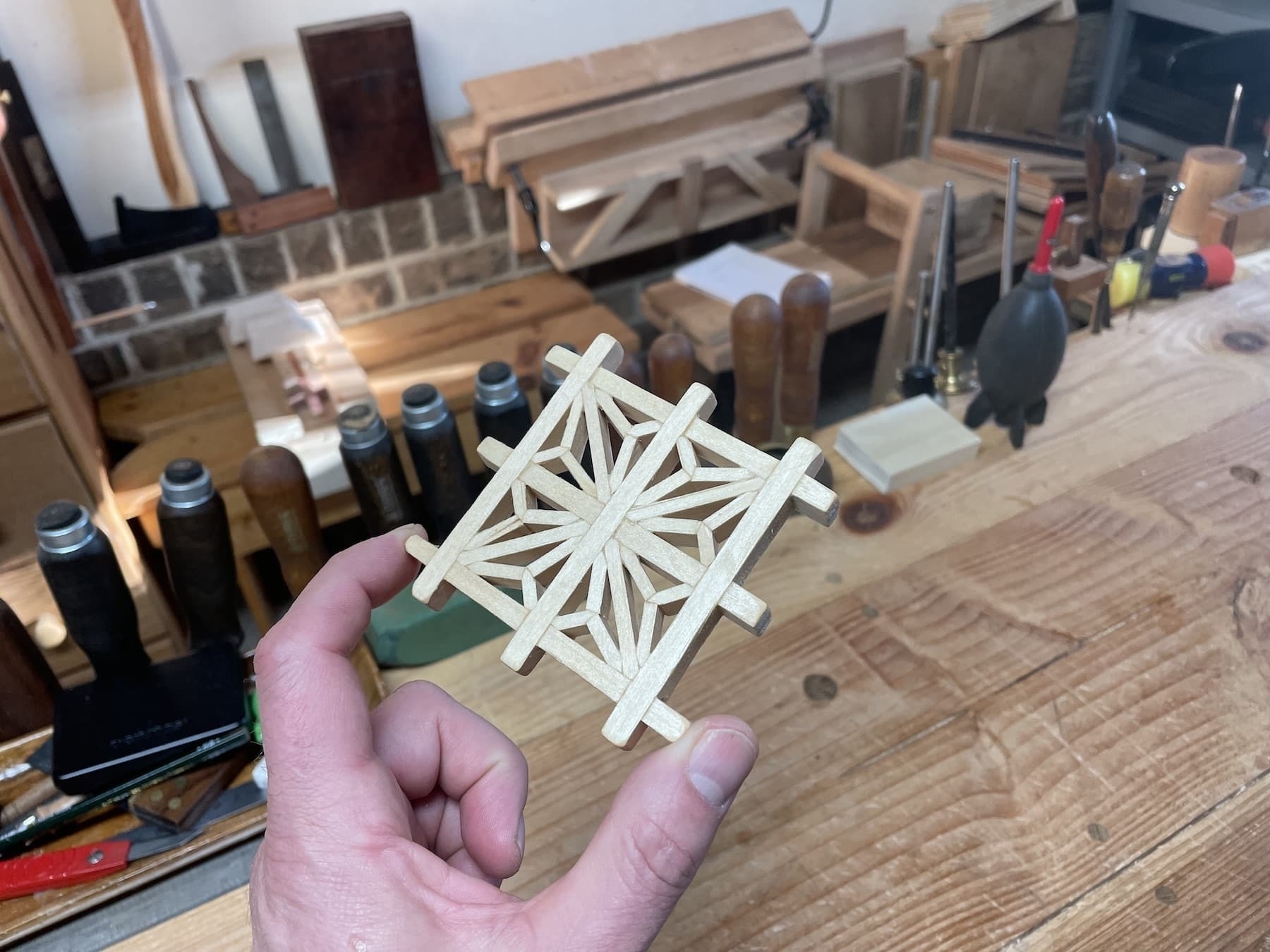

I decided to try my hand at making a small Kumiko ornament for the tree, as a first step in learning this process for later larger projects. This one took way more time than expected, because I needed to first create the jigs to cut tiny Kumiko strips. I figured out what I needed to do with an excellent book, Shoji and Kumiko Design: Book 1 The Basics by Desmond King, and very helpful YouTube videos from Adrian Preda. So I bought a big chunk of 5’‘W x 36’‘L x 1-1/16’’ basswood from Rockler and went to work. Here’s the finished piece.

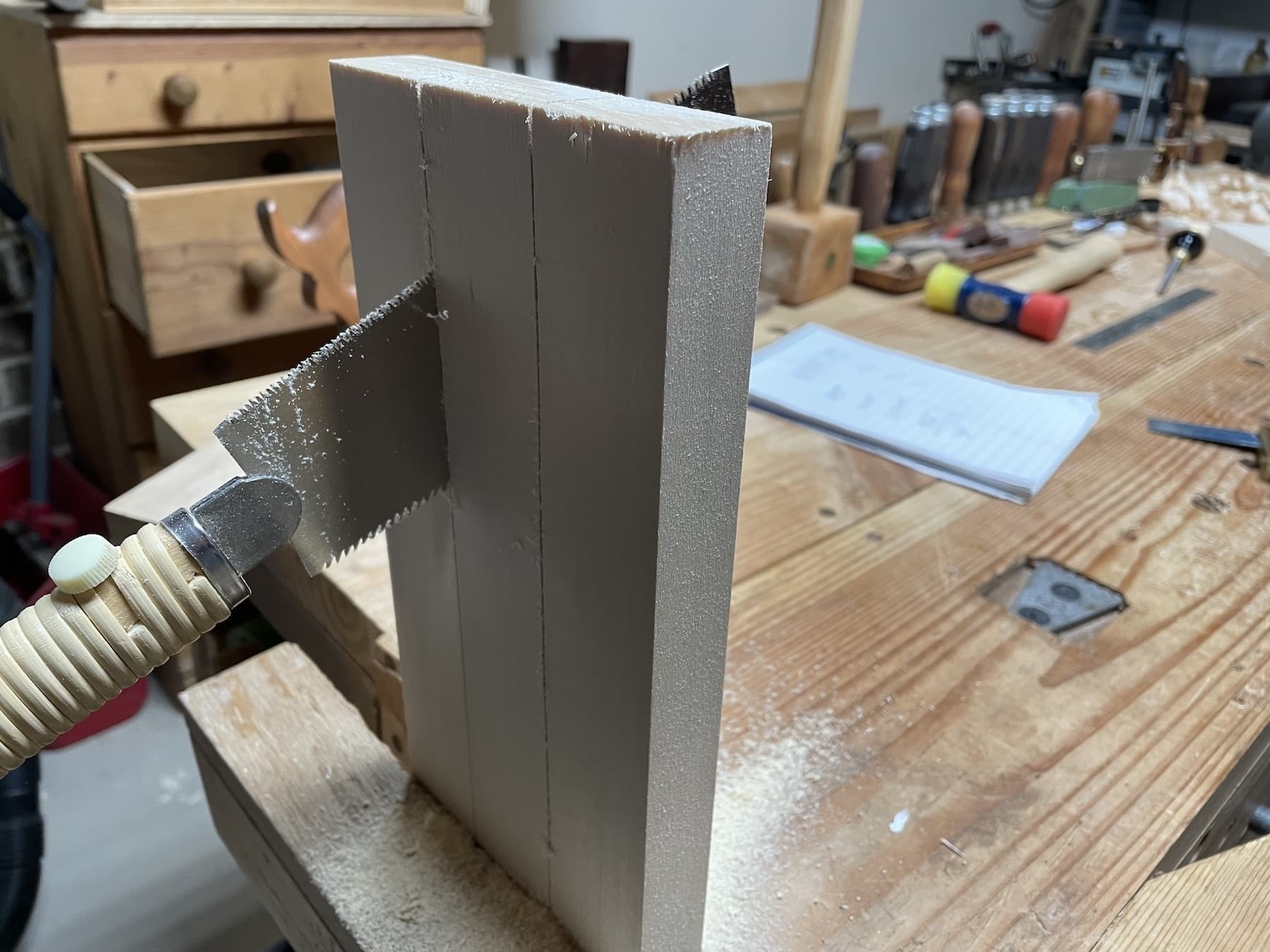

And here are the basic steps, starting with some pics of getting the basswood cut down to size. I started by cutting the board into thirds.

And then cutting those boards into thirds.

And then resawing all of those thirds.

I used two-sided tape to hold the wood while I cut the small strips out of the resulting boards, after planing them down.

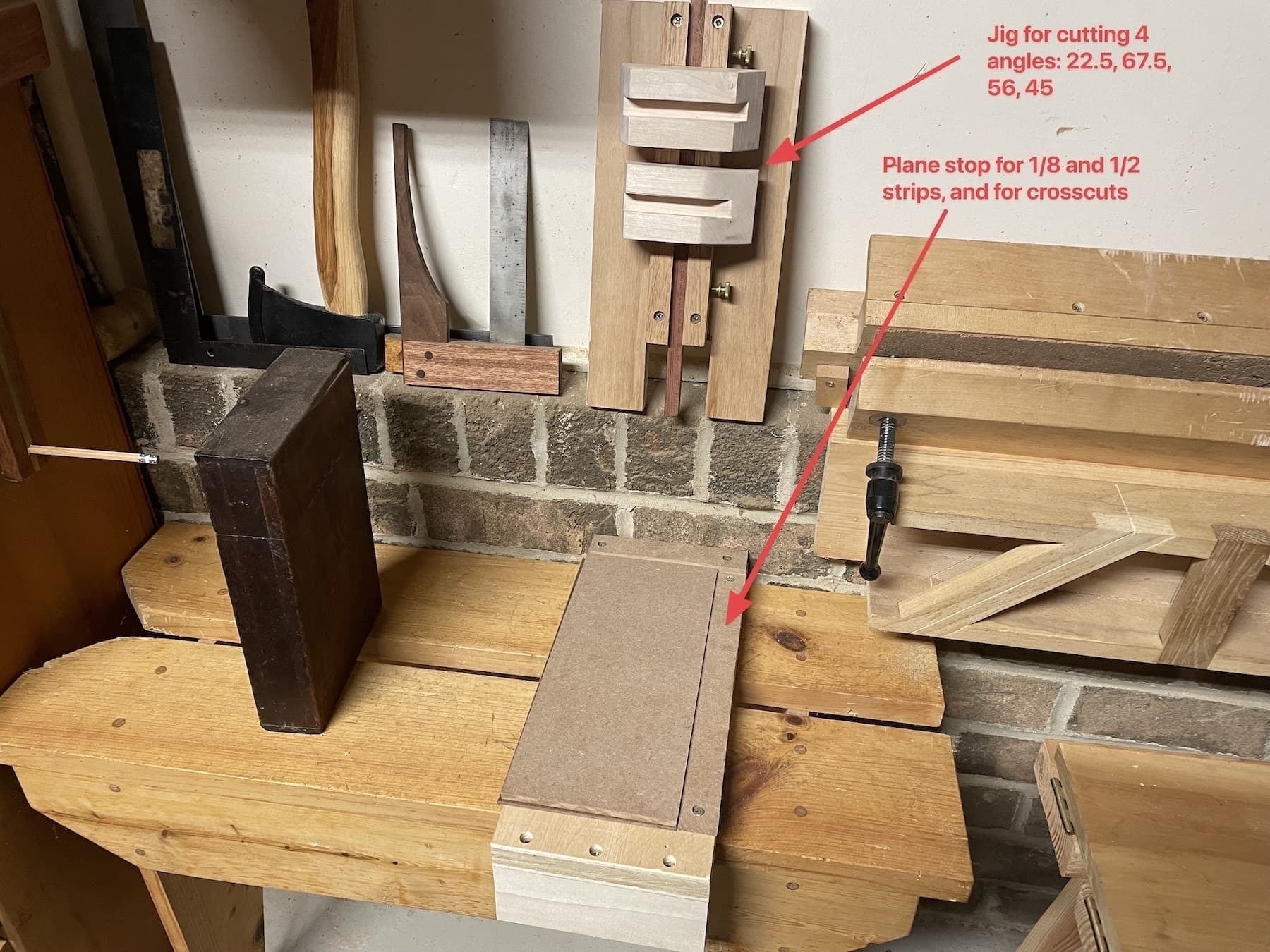

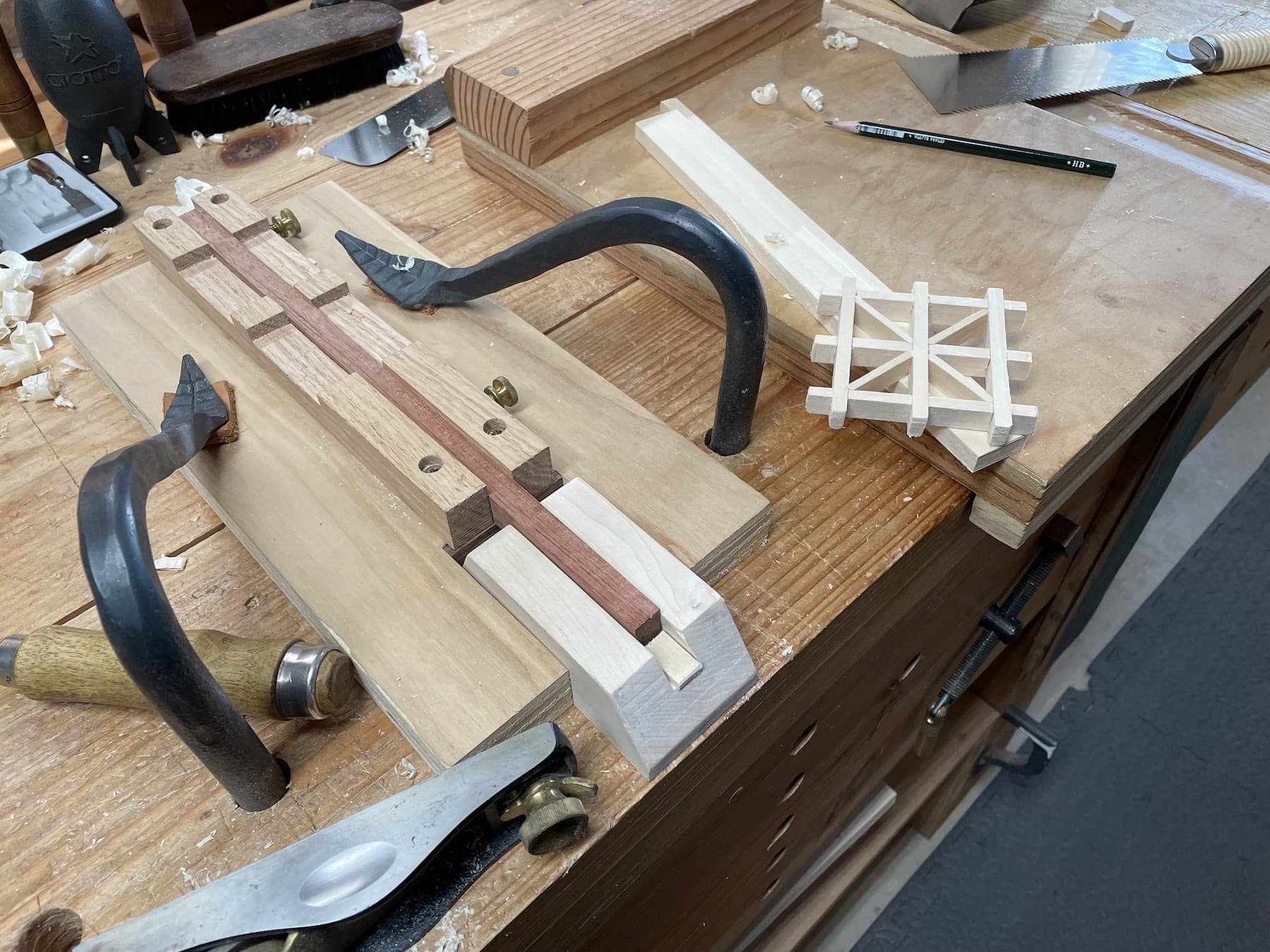

Here are the jigs I made, which took the most time in this project by far. The first one in the image below is for cutting the angles needed. I made this design up and I’m proud of it because it is all self-contained and can hang on a wall. You’ll see how it’s used shortly. The second jig is for planing the basswood down to uniform strips of 1/2" by 1/8"

Here’s the planing stop in action. The stop is 1/2" and two inserts are added as needed, one is 1/4" and one is 1/8". The side piece of MDF is used to cut the strips to length, after removing the inserts. So it does double duty.

Here’s how the angle-cutting jig works. The two short pieces of hard maple can be flipped around so each has two angles available. These fit into the jig with an adjustable stop for longer pieces. I hope to make larger Kumiko projects later on, so this gives flexibility. I can just cut new maple blocks if I need other angles to make other Kumiko patterns.

And here is my first Kumiko pattern (in the classic asa-no-ha shape). It is not perfect, but I’m happy how it turned out. I stuck it in the Christmas tree. Next year, I aim to batch produce a number of these for gifts. It was fun to learn how these work and was a challenge for hand tools only. Learning to do this with buttery basswood is a good way to go. I may next try one with walnut.

This is another going-away gift for a work colleague who left for another job. I’m incorporating a lapel pin in the project from my place of work, as I’ve found that cutting off the back pin part and insetting the small metal logo looks really nice. The box is poplar with a bubinga top and bottom. The gift is for someone who appreciates quality pencils, so this project was a great fit. The instructions for this box come from Renaissance Woodworking. This is a great, easy-to-do project. The pencils I bought for the box are Mitsubushi 9850. As an aside, I’ve found Mitsubishi 9800 pencils to be perfect for woodworking because the graphite is strong and makes dark lines.

Here’s a project using scrap walnut tongue-and-groove boards I was given by friend, which I used to create a small tray to dry herbs — my wife does a lot with herbal tinctures and such and needed a rack to dry some of the plants and mushrooms she collects while foraging.

This is the final drying rack:

The biggest challenge in creating this was the small size. Here is the walnut board I started with:

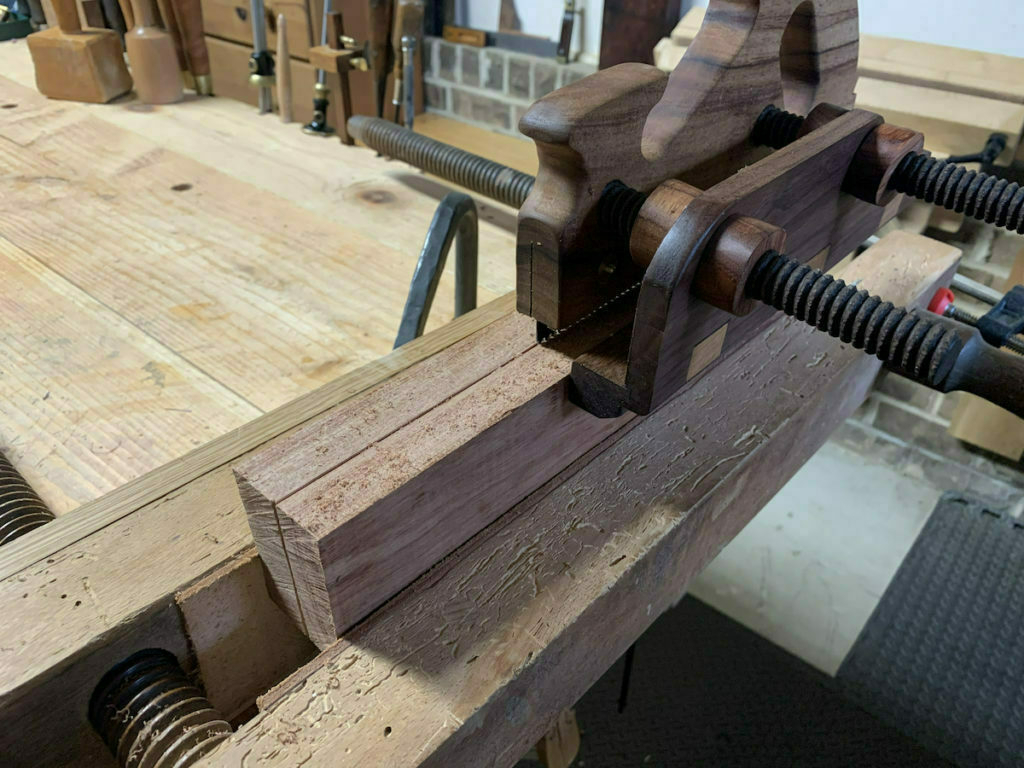

I used a holding tool I previously made called a Raamtang to keep all the small bits held firmly while I worked on them. This small wooden vise has proven invaluable over the years and is worth the time and effort to build if you create a lot of smaller projects.

I decided to make this a simple mitered box, but will add splines for strength. I cut the angles free hand and then dialed them in with this 45 degree shooting board I made. The final pieces are shown here resting on top of the shooting board.

I added a fancy curve to the four edges of the tray. I drew the curve on paper then traced it onto the wood. I used a backsaw to cut the to lines of the curve.

Then used a coping saw to get near my lines.

Then cleaned it all up with files and a spokeshave.

Here are the final curved edges.

After glueing up the frame, I added the splines with a contrasting wood (scraps of oak). I cut out the corners, cut the splines, then planed them flush with a block plane.

Then the final step was adding the chicken wire, for which I used some mesh from a big box store. The wire mesh is attached to the underside of the frame with wood strips half-lapped, glued and strengthened with small screws. That’s it.

A short article in the September/October 2021 issue of Popular Woodworking called attention to retired pattern maker Bill Martley’s project to reproduce the bronze head of the classic Studley Mallet, named after Henry O. Studley (1838-1925) that many woodworkers know from his famous and mind-blowing tool chest.

A member of my woodworking group spotted this article and suggested we embark on a group build. The bronze casting for the mallet cost $69 with shipping included. What an amazing opportunity and bargain! I received my bronze mallet head in the mail a couple of weeks ago and here’s the mallet I made with it using bubinga, bocote wedges, and a handle with inset waxed cord. I just love how this came out and I’m so grateful that Martley made this possible.

Here’s the mallet I made with the casting:

And I’ll briefly document the steps I took to make it.

First off, here’s the bronze casting as it arrived in the mail, along with the wood I selected to make the infill and handle. I went with bubinga.

Here’s the infill block sized to fit through the hole in the bronze head.

Next I chop out the through-mortise to match up with the hole where the handle will fit.

Here’s a view of the wooden insert with the mortise completed, mostly to show what the top and bottom of the casting looked like before I polished it up.

Now I began to shape handle, drawing out what I wanted in pencil.

Here’s a view of the handle, where I’ve cut out the slot to fit into the bronze casting. I used my large tenon saw for this. I squared it all up with chisels.

Here it is all rough fit together. Looking like a mallet now.

Next, I shined it all up using a Dremel. Wow, what a difference. I left it rough, because I liked the look of it.

Now, onto the handle. I cut it out roughly with saw work, then filed down with my beloved Auriou rasps.

Here’s the handle, showing the cuts for the wedged tenons that’ll go in the top to splay the wood out and hold it firm. The infill wood has not yet been cut to length.

Next, I decided to go with a wax cord wrap for the handle. I wanted it to sit flush, so I chiseled out the beginning and the end so it slopes inward from each side, so when I wrap the cord it’ll gently slope upward. This will form a nice place to hold it.

This image shows the beginning of the cord wrap, using tape to hold the ends in place. I wrapped the cord so tight, my hands cramped up.

And here a few glamour shots of the completed mallet, which I finished with boiled linseed oil. Oh, and I forgot to mention, I’ve added the wedges here. The two top wedges are tiny slices of bocote, which I think contrasts nicely with the bubinga. It was a fun project, and now I have a small mallet with a lot of mass. It’ll be a useful shop tool that I hope will still be in use by someone long after I’m gone.

The small bench is complete. We’re going to use this for putting on / taking off shoes in the mudroom. It’s been an interesting hand tool project, and I’m happy with how it came out. The main issues I had with assembly were some small joinery gaps, but I fixed these with hide glue and matching sawdust, and those gaps are not noticeable in the end. I have to say I’m not crazy with the sapele choice for the aprons, in retrospect. In the right light, the sapele looks kind of orange, so I think that’s what is bugging me. But it will mellow with time and I think it will age nicely.

I’m really happy with how the grain shows in the walnut, and the top of the bench really in particular shows some interesting light/dark contrasts with strong gray streaks. I also added a slight bow to each long side of the bench top, which gives the top a gentle tapered (subtle) curve at each end. I finished it with Osmo Polyx-Oil.

Here are some final assembly shots:

Here’s a shot documenting the tenon cuts for the legs.

And the mortises for the bench top.

I tapered the legs on the inside to help give the bench a slimmer profile from the front.

I locked in the knots on the bench top with some 5-min epoxy and it worked well. Since I just needed a little bit, I used the epoxy that I use for fly tying. I did this so that the knots don’t crumble over time.

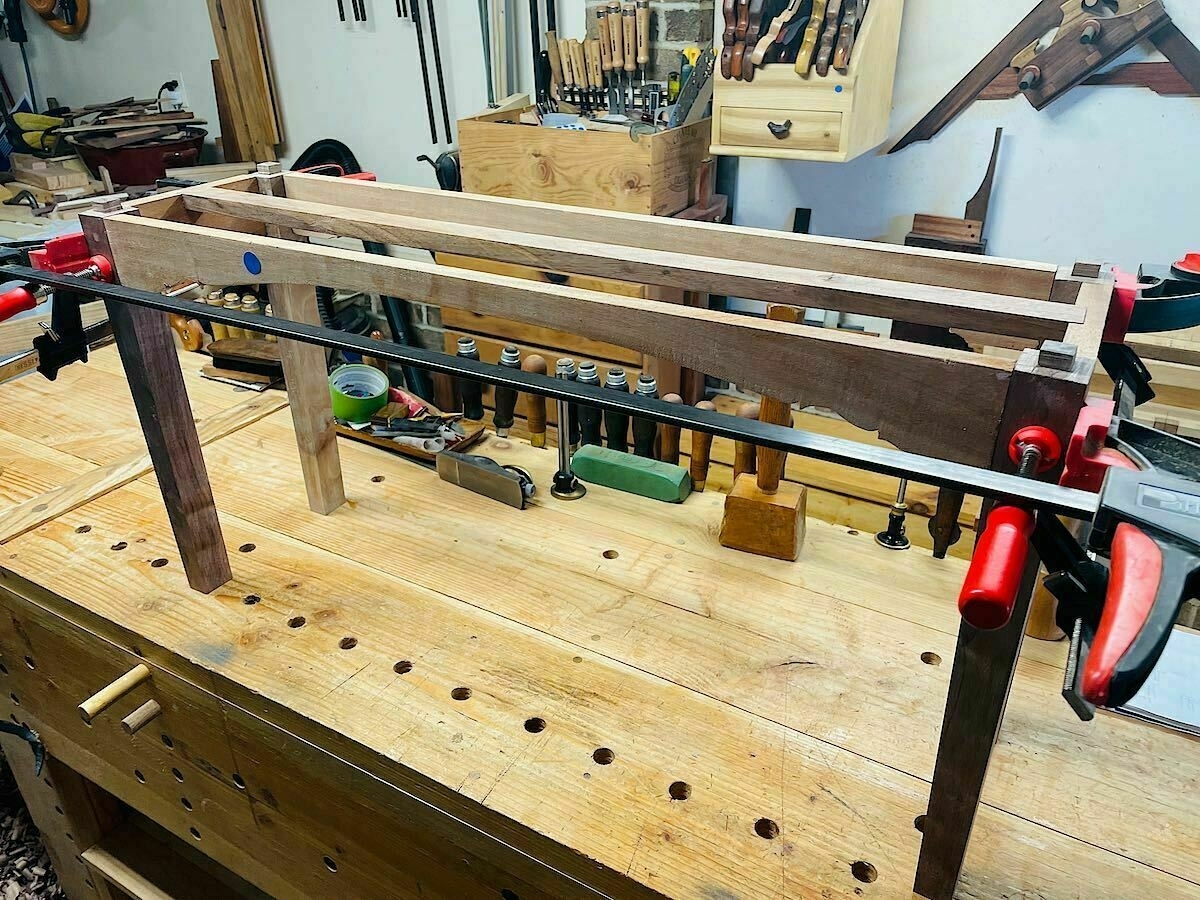

Here’s the dry fit of the frame.

And here’s some shots of the final bench after glue-up and finishing:

And here’s what I started with for reference: some old, incredbily warped slabs of walnut … and a new sapele board for the aprons. This transformation of chunks of wood to useable furniture is just magical to me. With some simple tool work and a plan, amorphous slabs can transform into something useful and beautiful.

My wife asked if I could make an extra-long shoehorn because she’s having some knee trouble. So I knocked out this project in an evening and it was a lot of fun.

I grabbed a scrap of cherry and roughly cut it to size using a rip saw and a spokeshave. Then it was mostly an exercise in filing.

I had a small shoehorn (store bought) to use as a reference. It occurred to me that this is kind of like spoon carving, but easier because there is no “front spoon edge” (so to speak) to a shoe horn, so I could just file it right down to get the desired shape. I had my significant other test it out several times to ensure I got the shape just right. The hardest part was ensuring it was as thin as possible at the edges of the “spoon,” but still strong.

I shaped the handle with block plane.

And finished it off with some Osmo wood wax, then wrapped the handle with blue waxed cord. I also added a loop to the end to hang it up out of the way. The lovely cherry wood grain was a happy accident. I had no idea that beautiful grain was hidden in that scrap of wood.

So I purchased the metal hardware to build a frame saw and kerfing plane from Bad Axe Tool Works. This was, for me, an intimidating project to build these tools using only hand tools. The plans I used are from Tom Fidgen's The Unplugged Workshop. The plane, in particular. Here's how that went.

I started with a small slab of Koa. It’s a special plane, so I decided to use some of the special wood I had bought when I had lived in Hawaii. I printed out the plan for the plane body at actual size and traced it out. I placed the plane blade here so I could better visualize what I was doing.

Here’s what it looks like all penciled out.

I cut out part of the body with a Carcase saw and my bow saw. Then came the scary part: carefully drilling out the holes for the special screws (forget the name of these) that would hold the blade in place.

You have to drill two holes on each side so that these screws sit flush. Not easy to do with with a hand drill, I discovered.

Here’s a View of cutting the inside handle hold with my bow saw.

And then some heavy and tedious filing to get everything down to the lines and smoothed out.

The threads in the plane body and the threads for the bolts are created with a thread cutter.

And here is how the screws are made for the arms. I used walnut because it’s pretty easy to work with, relatively speaking.

Rough cut for each wooden bolt. Then file them out to round them.

The completed arms with the bolts. These fit into the plane body like so, using the threads I created.

The most terrifying part of the plane build was cutting the kerf to fit the blade. It had to be perfect, so I created a jig to guide my saw and went really, really slow.

So I created this fence for the plane and glued it up, then realized I had made a terrible mistake. It’s way too thick. It needs to rest against the blade, but this fence hits the plane body and was a total fail. Not sure how I got to this point, but there it is. So what to do?

I could have started all over with the plane fence, but I decided to salvage it. So that’s why you see these interesting light colored things that look like joints that don’t joint anything. I installed a proper smaller fence arm. I tried to make the mistake look like a feature and not a bug. Here, you can see the blade is installed.

A view of the final plane from the another angle.

Here it is in action, cutting the kerf on a board that I’m going to resew with the frame saw. The wooden bolts lock the fence in place to get the desired line.

And that kerf gives you a good line all around the board to help keep the frame saw cutting true.

The result is resawed boards that are far better than I’d get than without using the Kerfing Plane.

I made some handy bench hooks based upon the teachings of Sloyd (which I don't know much about, but discovered is quite an interesting thing). Actually, learning about Sloyd may be the most interesting thing about this project. Anyways, these bench hooks are really useful to hold wood of different lengths on the bench for, say, cutting dadoes, or to hold up long pieces level when crosscutting on the hook I use for sawing, or for holding wood for paring.