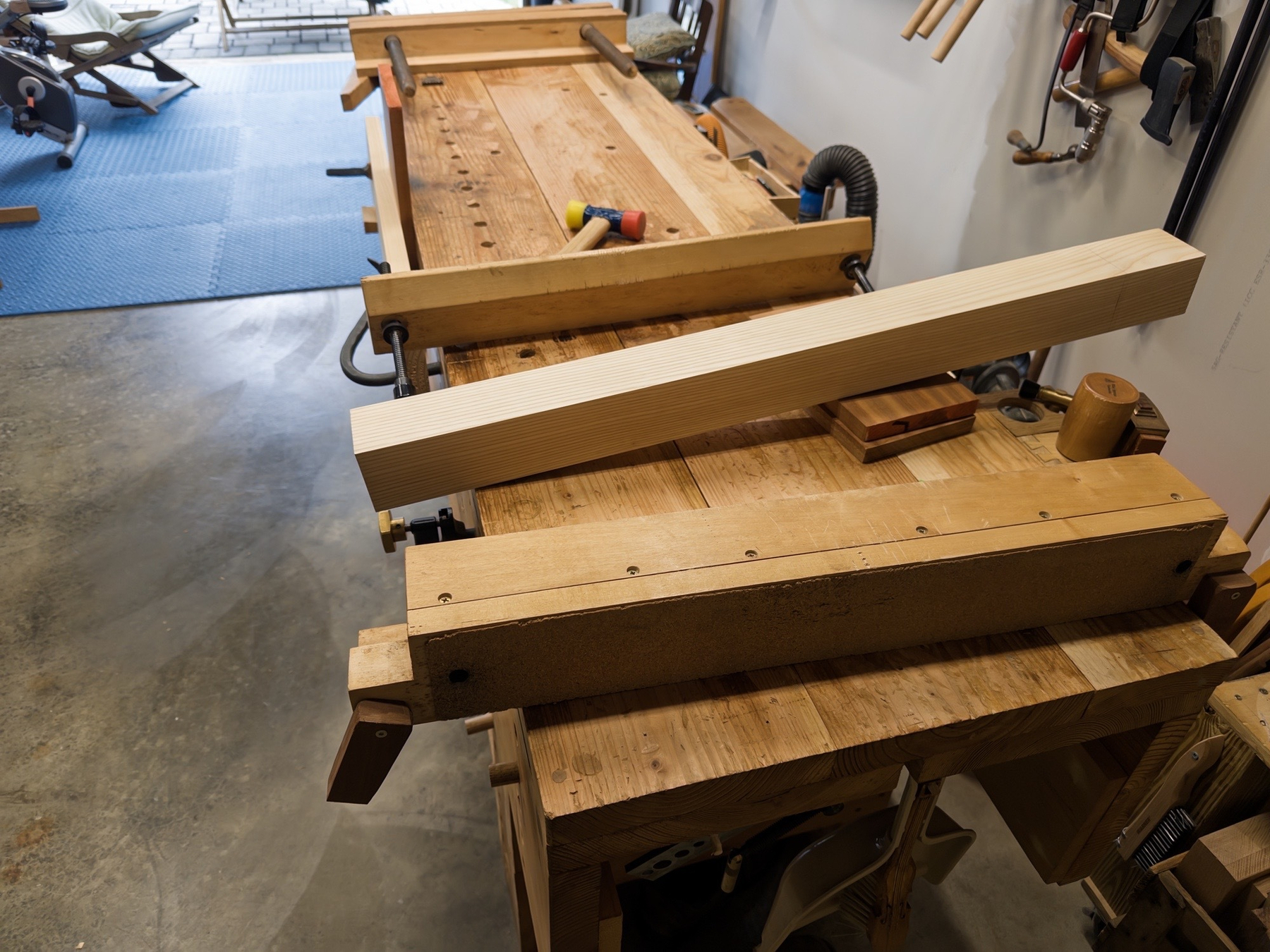

Final wood box with removable bottom drawer. Mistakes were made, but made it work. I planned to dovetail the sides, but grain directions were wrong. So I went with mortise/tenons, but they were shallow so I worried about strength. So I did something I rarely do: use hardware. I reinforced the corners with screws. Not my best work, but it will do the job! I’m happy with the curved corners, mostly (made with bow saw and my prized Auriou rasps from France).